Europa.–Make War.–Zenitism.

Newsletter 7

This is a regular feature wherein I write about some of the things I’m watching, reading, looking at, or otherwise consuming. Today’s newsletter is open to all, though most of these are at least partly behind a paywall. Consider subscribing today so you don’t miss anything–it costs about the same as if you bought me a single cup of coffee once a month.

Just a quick update about finding me: Some of you who know me from Twitter (or “X”, if you insist) might have noticed that I’ve temporarily deactivated my account there. At midnight on January 15th, the new Terms of Service came into effect, and there is no opting out. If you’ve used the site since, you’ve accepted them. But it’s not just that. Even just since January 1st, the place looks to have degenerated into an even more explicit hate machine; it now looks like a Silicon Valley social experiment in dissolving the capacity for human empathy. Meanwhile, whatever few benefits it once had for journalists–it has long been one of the fastest ways to get breaking news–are diminishing, as the quality of information on the site has been degraded. That said, I can’t really afford to stay off forever. The vast majority of my subscribers come from Twitter, and since I am doing this not just for fun but also to live, I need to use the site to share my work. But aware of the hazards therein, I will likely be cycling through more regular breaks. Just so you know and don’t worry if you see me missing periodically.

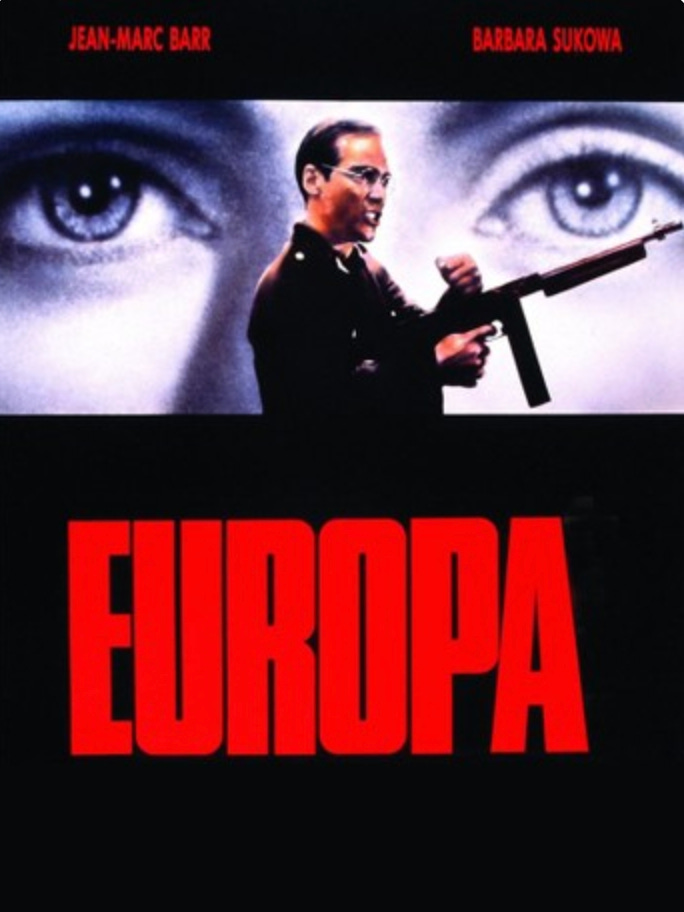

Europa

Europa (1991) is Lars von Trier’s best film. Years before he started making sadistic movies about female suffering like Dancer in the Dark (2000) and Dogville (2003), and before the crystallization of his proto-Nazi troll persona, von Trier made a lush, hypnotic noir about the American occupation of Germany. The film is almost entirely unrecognizable as von Trier; it’s also not an exaggeration to call it one of the most beautiful looking films ever made. But its disorienting political message, which casts doubt on the moral foundations of the post-war trans-Atlantic order, also feels eerily pertinent today.

The film’s setting is Germany in the second half of 1945, in the months after the German defeat–“year zero” as it’s called in the film. Much of the country has been reduced to rubble and the liminal “American Occupation Zone” has been set up atop the ruins. A naïve, idealistic young German-American named Leopold Kessler arrives, hoping to help his ancestral homeland after war; he is also eager “to show Germany a little kindness”. It’s a queasy foreshadowing, hinting at the doom awaiting the American do-gooder in foreign lands.

The young Kessler gets in touch with an uncle who works on the sleeper carriage of a train called Zentropa, where he takes a job as a conductor himself. He meets many pitiful characters on the moving train, including Jewish refugees and the beautiful daughter of the Zentropa’s owner with whom he begins a romantic relationship. While traveling through the wreckage of the Reich, we see dead bodies hanging outside the train window: victims of the Nazi guerrilla group Werwolf, an underground Nazi partisan movement established near the war’s end to terrorize allied soldiers as they advanced through Germany. In the years after the war, Werwolf cells launched sporadic attacks on the occupying forces, though they obviously never amounted to much. Without giving too much away, Kessler unwittingly gets involved with Werwolf; his naïve idealism and passivity have made him an easy mark for manipulation.

Von Trier is preoccupied with the concept of neutrality. He despises it. In one scene, a Catholic priest says that being neutral is the worst sin. Fighting for a cause, no matter how bad, is better than fighting for nothing. You can see how this line of thinking would appeal to a certain kind of compromised individual in post-WWII Germany. I immediately thought about recent speeches by contemporary European leaders like Germany’s ex-Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, who makes use of that famous quote by Desmond Tutu, “if you are neutral in situations of oppression you are choosing the side of the oppressor.” I had always thought that this position was rooted in revulsion at passivity in the face of Nazi horror, a moral argument for standing up to evil. But after watching the former Nazis in Europa employ a similar rhetoric, I do wonder if it’s also something more self-exculpatory and morally dubious: a psychological defense against guilt that celebrates militarism or “action” for its own sake, thus placing Nazism above neutrality in an imaginary moral hierarchy.

And yet, Europa is not the Nazi-sympathizing film you might expect from a director who once told an audience at Cannes that he “understood Hitler”. (He later said the comments were taken out of context). Von Trier very clearly judges Germans as guilty. He is just not so convinced of American innocence. In Europa, the Americans are untainted by the recent war (and only because it hardly touched our shores), but they slip easily into collaborationism, and later into Nazi violence. The system they’ve imposed on the docile and compromised German populace looks democratic and just from a distance, but up close, it’s filled with holes. In the American Occupation Zone, the Americans initiate a denazification program, but it’s clearly very corrupt. One American official arranges for a Jewish thief to write a false testimony attesting to the supposed wartime benevolence of a Nazi; in exchange for his cooperation, he is released from jail. The entire post-war order, von Trier appears to be saying, is built upon these rather shaky foundations.

Europa is fascinated with in-between spaces, best embodied in “the zone” and the train. But there are others: the film exists in a place between war and peace, between the Nazi regime and the democratic one, between departure and destination, between perpetrator and victim, between sleep and waking life, between good and evil, and between past and present. The Zentropa itself used to carry Jews to concentration camps; in peacetime the train’s been repurposed to carry third class passengers and corrupt Americans. In Europa, there are no clean breaks with the past.

Many people, including me, have written a lot about the vaunted “post-1945 liberal order” and trans-Atlantic relationship in recent months and years. Europa takes you to the very first months of that era and to its source, bearing witness to its original sin: moral corruption, superficial denazification, and continuities between regimes. The film was released in 1991, just a few months before the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, the founding document of the European Union. During a decade distinguished by unipolar optimism and Euro-Atlantic confidence, von Trier correctly identified something dark and atavistic still lurking beneath the surface.

Make War

“We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

We will destroy the museums,

libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every

opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.”– Manifesto of Futurism, Filippo Marinetti, 1909

The Italian Futurists venerated war above all things. They saw it as an engine of progress and a cleansing fire. Founded by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, futurism was one of the early 20th century’s most incendiary art and social movements. The Futurists famously celebrated speed, youth, vitality, technology, destruction and masculinity; they reviled the feminine and feminism, along with Italy’s accumulated “ancestral lethargy”. A decade after the founding of futurism, the movement merged with Mussolini’s fascists.

The futurists and fascists had much in common, and nowhere more than in their glorification of war. In 1914, as Mussolini enjoined Italy to enter the war, he said, “it is blood which moves the wheels of history”. Marinetti could have said it himself.

I remembered the Italian futurists when I read the piece “The Orbital Authority” by Curtis Yarvin, the pro-monarchy software engineer-turned-MAGA court philosopher, who used to blog under the name Mencius Moldbug. The piece ran last year in Palladium Magazine, which is based in Silicon Valley and reportedly funded by Palantir founder Peter Thiel. (The publication’s tagline is “governance futurism”). Here’s Yarvin:

War is again the father of all things. Peaceful empires stagnate and grow decadent. Wars generate ideas, art, technology, and progress. Forget the UN—how much of the postwar 20th century was created by the war? Every time we fly, we are flying on a peacetime conversion of WWII air force technology. Without war, would we even have jets? Why?

Again we have the futurist-fascist veneration of war as generative rather than destructive. The post-WWII order is built on the latter perception; the idea that, in the West at least, war is always destructive and must be avoided at all costs. The Silicon Valley right (or Tech Right; I’m not sure if we’ve established a single name to describe the powerful pro-Trump cohort within the liberal Bay Area) would also lament the supposed “globalist” neutering of nationalism, seen as the driver of the 20th century’s most destructive wars.

Some may be tempted to write off a single piece by Yarvin, but this attempt to shatter post-WWII taboos is integral to the entire MAGA project. What’s particularly unsettling is that they are actually quite sophisticated in this; they know how to weaponize language and jargon to soften our defenses to their violation, and perhaps even to welcome it as relief. Alexander Karp, the CEO of Palantir, wrote his PhD dissertation on a controversial speech delivered by German writer and former Nazi Martin Walser in 1998. Upon accepting the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in Frankfurt, Walser spoke of the supposed instrumentalization of Holocaust memory as “a means of intimidation or moral bludgeon”. In other words, Walser shattered the taboo on the way Germans are supposed to talk about WWII:

No serious person denies Auschwitz; no person who is still of sound mind quibbles about the horror of Auschwitz; but when this past is held up to me every day in the media, I notice that something in me rebels against this unceasing presentation of our disgrace. Instead of being grateful for this never-ending presentation of our disgrace, I begin to look away. [I would like to understand why the past is being brought up in this decade more than ever before.] When I notice something in me rebelling, I try to seek out the motives of those holding up our disgrace, and I am almost happy when I believe I can discover that often the motive is no longer keeping alive the memory, or the impermissibility of forgetting, but rather the exploiting of our disgrace for present purposes.

Later in the speech, Walser invokes Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil”, but instead levels the charge that there must be a “banality of the good” in reference to the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, which had not yet been built but was being discussed:

Posterity will be able to read one day, in all the discussions concerning the Holocaust Monument in Berlin, what people stirred up when they felt themselves responsible for the conscience of others: paving over the center of our capital to create a nightmare the size of a football field. The monumentalization of our disgrace. The historian Heinrich August Winkler calls this “negative nationalism.” I dare to assert that this is not a bit better than its opposite, even if it appears a thousand times better. Probably there is a banality of the good too.

In his 2025 book The Technological Republic, Karp had this to say about Walser’s speech (emphasis mine):

The moment was deeply cathartic for nearly everyone listening, who, according to several accounts, stood up at the end of Walser’s speech to give the author sustained applause. He had articulated the forbidden desires and feelings of a nation, and in doing so relieved an immense amount of internal dissonance for his audience, most of whom had been immersed in a culture in which speech had been tightly patrolled and monitored for even the slightest signs of deviation from the received wisdom, the national consensus.”

This is what I believe MAGA and its Silicon Valley brain trust are doing: weaponizing language in such a way that allows us to overcome the taboos around war put in place after WWII, and, for some, to experience the violation of those taboos as a resolution of internal tension, as a kind of relief. Of course, many readers might be confused by this. After all, the United States has hardly been reluctant to wage war all around the world. But that was slightly different: Before, there was at least some pretense to multilateralism and “respect for alliances”. Now, we’re being psychologically primed for an entirely new era of unilateral warfare.

Zenitism

Re-reading the Futurist Manifesto, I was reminded of another early 20th century avant-garde art movement called Zenitism, which was most active during the 1920s. The movement was centered in Zagreb and Belgrade in what was then “first Yugoslavia”, and published a magazine called Zenit .

Zenitism was inspired in part by the explosion in orientalist writings on the Balkans that accompanied WWI. The movement then sought to “reclaim” those stereotypes and use them, in a mocking yet provocative way, “against the West”. As the movement’s manifesto read, “Let us destroy civilization through new art!”

Iva Glisic and Tijana Vujosevic have described Zenitism as:

the attempt by Yugoslav poetic and political enthusiasts to climb to the zenith of European civilization and disrupt it by ‘Balkanizing’ the Old Continent. Most importantly, they aimed to transform European clichés of Balkan backwardness and belligerence by identifying with “the Balkan” and presenting him as what they termed the “Barbarogenius.” This new type of man was to be seen as a figure whose fresh, primitive and creative genius would conquer and rejuvenate tired European culture.

Excellent remarks on futurism and militarism - I was reminded of German Nihilism by Leo Strauss, have you maybe read it?