Korça, Albania: Banned Thought and the Ghosts of Glass

I have spent much of my time in Korça, Albania reading “banned or difficult-to-find” communist literature. The supplier of this contraband is the fantastically retro bannedthought.net. Redolent of a turn-of-the-century GeoCities website, bannedthought.net claims no affiliation with any party, revolutionary organization or network, but is clearly sympathetic to Enver Hoxha. Adding to the site’s clandestine allure is the fact that it is in constant threat of disappearing: as the name suggests, there are some powerful forces that want it gone.

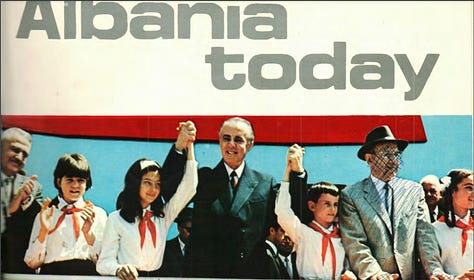

In recent weeks, I have scrolled through dozens of pdfs of Albania Today, a lush, theory-heavy magazine published from 1971 until the dissolution of Albanian communism began in 1990. Albania Today billed itself as “a bimonthly political and informative review”; it was meant to provide foreigners with a window into “Albanian reality” and the Party of Labor of Albania’s perspective on world affairs, art, and culture. Alongside the latest reports on agricultural yields and the adoption of industrial fertilizer, you can find literary criticism and short stories by Booker Prize recipient Ismail Kadare written in tortured accordance with Hoxhaist Thought, a “humor” section — explicitly labeled as such — with political cartoons satirizing the hypnotized masses in capitalist countries, and savage attacks on virtually the entire rest of the world. Hoxha and his followers were, among other things, fervently devout haters. Almost no one was spared the Albanian communists’ wrath — not the Yugoslavs (“Titoites”), not the Soviets after Stalin (“Khrushevites”), not the Chinese, and certainly not the Anglo-American imperialists. Bannedthought also hosts Hoxha’s entire body of work, which was voluminous. (The Titoites, his blistering treatise on the revisionism, conceit, and treachery of Tito’s Yugoslavia, is over 600 pages long).

It is easy to sneer at all the suffocating dogma and eccentricity of Albanian communism — Albania would remain Stalinist for more than three decades after Stalin’s death, and is often exoticized as “the North Korea of Europe” — but I am prepared to admit that there is something appealing in some of what is presented in the pages of Albania Today. There is a sense of optimism that suffuses the works, and the promise of resurrection from the ashes of war.

Then, a few weeks into my stay in Korça, the news came that Jared Kushner had plans to develop the Albanian coast, along with the remnants of the Yugoslav People’s Army headquarters in Belgrade. I couldn’t help but think that maybe Hoxha had a point. The renderings for Kushner’s coastal development look like a crypto bro’s dream: a nightmare digital nomad hub, or gauche condos for the Silicon Valley pseudo elite. I began to understand why bannedthought.net was considered dangerous. Hoxhaism wasn’t without its logic: self-reliance, or as Albanian economists called it, “relying on our own forces”, was a lesson learned from the bitter experience of foreign betrayal, exploitation and occupation. But beyond this admittedly superficial understanding, there were other reasons that reading such things felt fraught with temptation. During any internet deep dive into fringe material, one always feels the pull of the edge, and the attraction in allowing oneself to tumble over it.

I commenced my bannedthought.net binge trying to find information about something else that seemed relegated to the realm of secret knowledge: the spectral remains of the old factory on the edge of town. I stumbled on it one morning by accident, and it left me with a haunted feeling that refused to leave me. One day in early March, I wandered a few kilometers up the Bulevardi Fan Noli, a street named after the Albanian national hero and founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church. I walked past the century-old Korça Brewery, which makes beer from the waters that flow from Morava Mountain. Just beyond the brewery on my left, I saw a boundless yellow field open up which let me know that I had reached the edge of town. Set very far off the road, deep within that field, was an abandoned villa. It stood completely alone. Grand and palatial, even in its reduced, decayed form, it seemed very out of place. Its aura was forbidding, and I approached it with caution. Up close, it was even more extraordinary: three stories tall, with a stately entrance and multiple balconies. Most of its windows had been boarded up with bricks. Though thoroughly abandoned, it looked like something that had been preserved due to superstition. Clearly someone important had lived in it once.

Beyond the derelict villa was something perhaps even more striking: the remains of a very large factory, with some of its smokestacks still intact. It emanated a foreboding too, but also an industrial majesty. I walked toward it, mesmerized and afraid. I wondered what it had produced while it was still alive. Looking down at the ground as I got closer, I got my first clue: everywhere, seemingly embedded in the earth, were raw chunks of some kind of material, a radiant emerald green. It looked almost precious, the stuff of gems, and seemed like it had been abandoned in a hurry.

The fields of strange, viridescent crystalline matter led up to a no less spectacular site: smokestacks and brick factory buildings, some relatively whole, others skeletal. I stood still for a few minutes and imagined the scene coming back to life, like a flashback sequence in a movie: workers walking up to the factory gates early in the morning, lunches packed by the wife or eaten in a packed canteen, workplace flirtations on the factory floor, camaraderie, promotions, birthdays. Thousands of people had likely passed through this place, dedicating much of their lives to it, and now it was nothing.

Watching over the neglected ruins of Albania’s industrial heritage, on the mountain above, was an Orthodox church and an imposing cross: Glory to Labor supplanted by Glory to God, the kind of capitalist superstition that Hoxha so despised. Religion was banned in Albania in 1967, and it was only after Hoxha’s death in 1985 that a more tolerant line on religious practice was adopted. The Albanian communists saw religion and revisionism as intimately linked; the Soviet Union’s acceptance of mosques and churches, along with the publication of associated religious materials was, in their view, evidence of Khruschevite impurity. It allowed for what Hoxha called the persistence of the “reactionary and obscurantist rubbish of the Middle Ages”. The enormous cross sitting high above the ruined factory therefore seemed like a symbol of triumph. Looking up, I wondered what it must have been like for believers to hear church bells and the call to prayer for the first time after all the years of silence.

I wanted to search for remaining signs of life among the ruins. The building furthest from town seemed the most intact, so I walked towards it. I first took a look through a broken window. Standing on my tip toes in the high noon sun, I saw nothing inside but black. Suddenly, I felt a wave of pure terror. I turned my back on the factory grounds and bolted in the opposite direction across the field. As I walked back along Bulevardi Fan Noli towards town, I could not shake the feeling that I was being followed.

The feeling did not leave me. It pursued me the entire time I was in Albania. And the more I read about the field beyond the brewery, the more unsettled I felt. What struck me most was that it was a familiar dread: It was the same visceral terror I feel when I’m home in suburban California; I detected the same sense of an extinguished dream, the dereliction of a utopian vision, and neglect. I wanted to understand this confounding sameness but I also wanted to avoid understanding it, because thinking about it too much felt like looking directly into darkness. And as curious as I was, I knew there was something there that I didn’t want to see.

It was easier to focus on the concrete, or at least what remained of it. With the help of bannedthought.net, I learned that the brilliant emerald material embedded in the soil was glass. It was a glass factory. The facility in Korça was established in 1954 and was the first of its kind in Albania. Two more glass factories were later set up in Tirana and Kavaja. All of them would close during the 1990s, as Albania underwent rapid deindustrialization, with most of its factories left abandoned. Much of it has since been scrapped and sold for parts. Over 30,000 people in Albania today reportedly find sustenance solely through the collection of industrial scrap. For its part, the old glass factory grounds on the outskirts of Korça are currently for sale on an Albanian version of Craigslist. I sent a message to the owner on WhatsApp and inquired about the price; the entire site would cost about 130,000 euros.

The villa, I learned, once belonged to one Selim Mborja, a wealthy philanthropist who opened the brewery with an Italian business partner. He left Albania when the communists took over, fleeing first to Thessaloniki, where Hoxha’s men had plotted to kill him, and then on to Istanbul, where he took Turkish nationality. Selim Mborja’s sister was reportedly married to Tefik Mborja (no blood relation), the General Secretary of the Albanian Fascist Party. After taking power, Hoxha seized the villa for himself. It became his residence in Korça.

I thought that learning this history would banish the haunted feeling, but it only enhanced it. I could not help but think of the obvious thing, which was Derrida’s Specters of Marx and the incantation, “I would like to learn to live [with ghosts]”. I wanted to find a way to live with these remains, to dignify them. What I needed to find was something precious in the ruins, a redemptive element in the blackness.

I found it in the glass. Korça glass did not just have a history, but a well-tended to present. A native son of the city by the name of Mirgen Shamlli has amassed a collection of 6,000 pieces of Albanian glass, which includes both wares and figurines. These span the brief history of industrial glass production, from 1954 and 1992, and have recently been published in a catalog. Shamlli described the care that went into his work. “The enlargement of this collection year after year felt exactly like the process of putting mosaic pieces together, because emphasis was given on highlighting the importance of the aesthetic value of the Heritage: initially, the objects might look ugly, unimportant and naive, but [their] complexity in the bigger picture [leaves you] astonishingly speechless.” Discovering Shamlli’s collection put my mind to rest. For the ruins, there was a kind of afterlife.

Great to read from you again. And what a moving and insightful piece.

Makes me wonder what you would ferret out if you spent more time in Vietnam. Few short term visitors know much of anything and do not push themselves to find out more, I have had a few interesting conversations with them but not many.