In late 2021, I wrote a series on the German Green Party on an old platform that I unpublished when I migrated to Substack. Recently, several people have asked me to republish that series here, so I’ve decided to do just that. I’m actually not yet sure if I’ll republish the entire series or just parts of it, but I’ll begin with the initial introductory piece today. A few comments first: I wrote this series in late 2021 because it was clear to me then that the German Green Party’s dramatic rise and particularly its capturing of the foreign ministry was significant and likely foreshadowed the emergence of a more militaristic Germany and Europe. Of course, this is exactly what has happened, and far beyond what I imagined was possible then. At the same time, I wanted to highlight the German Greens’ history of pro-pedophilia activism, because I think it’s an important indictment of the left’s penchant for “shattering taboos” for the sake of shattering taboos (often under the banner of sexual liberation), a mindless, destructive ethos that has attracted many predators to various movements and projects.

Anyway, here is the first post of the series in its entirety, originally published in December 2021:

Few may have noticed, but a pro-war Germany–a belligerent Germany–is back. The war taboo that dominated the country’s politics post-1945 is now gone. This shift has passed with surprisingly little commentary given its potential implications. Responsible for this pro-war reorientation is the rise of the German Greens, the party that pushed for the first use of German military force since the Nazi era against Yugoslavia in 1999, and who now command five ministries. Their ascent has other kinds of significance beyond Germany, as the Green style of politics is currently being replicated across Europe. In other words: we are all living in the German Green Party’s world now. We should try to understand who they are and how they got here, because they and others of their ilk are going to be with us for a long time.

The transformation was formalized in September with the country’s parliamentary elections. Across the Atlantic, all eyes were on the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), truly Washington’s dream party. The Greens’ agenda is neoliberalism and war (in the name of “human rights”), but lacquered in a radical “green” gloss. The party derives this radical sheen from its founding members’ association with the protests of 1968. Beyond that, there is also a purported commitment to environmentalism, fighting racism and xenophobia, and championing militaristic gender equality (i.e. “women can be defense ministers too”). But this supposed radicalism is also tempered by “pragmatism”, evident in slogans like Radikal ist das neue Realistisch.

In the run up to the election, the Greens were treated as inevitable winners by the United States. Washington and the liberal press did little to conceal their obvious excitement at the prospect of a Green victory. As Joachim Jachnow wrote in his exquisite 2014 essay on the Greens for New Left Review, “The Greens are the American Embassy’s favorite German party nowadays. And why not? The Green Party has reduced the struggle for universal emancipation to the small change of ‘organic’ and ‘fair trade’ consumerism.”

The feeling is apparently very mutual. In the months ahead of the vote, party co-leader Annalena Baerbock, 41, made the rounds pledging her support for Joe Biden and the transatlantic relationship, and speaking at events alongside people like Madeleine Albright.

Hopes had been high all year that the Greens would dominate the vote and even secure the Chancellorship, but a last-minute plagiarism scandal (practically a rite of passage for German politicians) hobbled Baerbock, and the party yielded a more modest third-place finish. The SDP (Social Democrats) won 25.7 percent of the vote, Angela Merkel’s CDU netted 24.1 percent, and the Greens got 14.8. Significantly, the Greens did come out the kingmaker, and this meant that they were able to take five ministries, including the ministry of foreign affairs.

All around, it seems to be a perfectly respectable result for a party once stigmatized as an anti-nuclear hippy drum circle. The Greens may even have a fighting chance at the Chancellery in 2025, provided the skeletons in their closet don’t get in the way.

***

It has been a long, heady journey to the heights of power. The story of the German Greens begins in 1968. Many of its most prominent founding members, including Joschka Fischer, Jürgen Trittin and Daniel Cohn-Bendit, were left-wing militants. Fischer worked at Karl Marx book store in Frankfurt and participated in civil unrest in Stuttgart. Cohn-Bendit was a highly visible protest leader and acquired the nickname “Danny the Red”. In the 1970s, Trittin was a member of a Stalinist organization called the Communist League.

The Greens knitted together the disparate social movements that grew out of the protests of the 1960 and 1970s. The political scientist Horst Mewes described the first Green Party program of March 1980 as envisioning as “a pacifist, environmentally compatible welfare state, with totally emancipated self-governing green republics existing autonomously in a pacified world of international mutual assistance and political harmony.” It was utopian through and through.

This also extended to the realm of sex, an area of significant importance to the ‘68ers. As Klaus Theweleit, author of the book Male Fantasties, wrote of the West German student movement, “a special sort of sexual tension was the ‘driving force’ of 1968.” This ultimately led the Greens to assume a rather repulsive position: support for pedophile rights.

It sounds like a right-wing meme but there was a philosophy underpinning all of this. The protests of 1968 had resurrected the works of Austrian communist and Freud disciple Wilhelm Reich. His Mass Psychology of Fascism outlined the alleged connections between the attraction to authoritarianism and the societal oppression of sexuality. Copies of Reich’s pamphlet Sexual Struggle of Youth were sold in student dormitories, and his words were reportedly scrawled on the Sorbonne. Reich had also underlined the supposed connection between the suppression of children’s sexuality and obedience to authoritarianism:

“Suppression of the natural sexuality in the child… makes the child apprehensive, shy, obedient, afraid of authority, ‘good’ and ‘adjusted’ in the authoritarian sense; it paralyzes the rebellious forces because any rebellion is laden with anxiety; it produces, by inhibiting sexual curiosity and sexual thinking in the child, a general inhibition of thinking and of critical faculties. In brief, the goal of sexual suppression is that of producing an individual who is adjusted to the authoritarian order and who will submit to it in spite of all misery and degradation.”

These ideas gained traction in West Germany in the 1970s, when young people were seeking explanations for their parents’ obedience to the Nazis.

From the party’s first convention in the southeastern city of Karlsruhe, participants spoke of pedophilia as a human right. At the 1980 conference, the Greens advocated for the removal of two sections of Germany’s penal code that make sex between adults and children illegal. Regional chapters in North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Bremen, Hamburg and Berlin passed similar decisions.

Then there were the experiments. Among them were the “Indian Commune” in Nuremberg, where homeless children were invited to live with adults. Some of the children, referred to as “Stadtindianer” (city Indians), were reportedly subjected to sexual abuse. They were also dispatched to protest in favor of the legalization of pedophilia, sometimes at Green Party events. Then there was the Kentler Project, which sent Berlin street children to live with pedophiles. Program head Helmut Kentler held a top position at Berlin's center for educational research. He believed that sex between children and adults was entirely benign. Finally, there was the anti-authoritarian kindergraden or Kinderladen. These schools aimed to put Reich’s teachings into practice, as a sort of social reconditioning experiment for German children. A lax attitude towards sexual contact between adults and children prevailed. The Kinderladen promised such radical transformation that Cohn-Bendit spent two years working in one. He wrote a rather graphic and disturbing account of the experience in the August 1976 edition of the now defunct publication das da:

“My constant flirt with all the children soon took on erotic characteristics. I could really feel how from the age of five the small girls had already learnt to make passes at me. It's hardly believable. Most of the time I was fairly defenseless.”

In a later passage he wrote:

“It has happened to me several times that a few children opened the flies of my trousers and started to stroke me. I reacted differently each time according to the circumstances, but their desire confronted me with problems. I asked them: ‘Why don't you play with each other, why have you chosen me and not other children?’ But when they insisted on it, I then stroked them. For that reason I was accused of perverted behavior.”

When the passages surfaced in 2001 (unearthed and leaked to the press by Bettina Röhl, daughter of Ulrike Meinhof of the Red Army Faction), Cohn-Bendit said that they were written as a “verbal provocation”:

“It was meant to illustrate the difficulty of the educator in bringing up children: how does one accept that children have a sexuality, and also to recognise the resistance against which educators have to work,” Cohn-Bendit said.

But in 1982, Cohn-Bendit described pedophilic acts on a German talk show. "When a little girl who is five or five-and-a-half starts undressing you, it's fantastic. It is fantastic because it's a game, an absolutely erotic-manic game," he said.

Other leading lights of the Greens were associated with pedophilia. One of them was activist Volker Beck, who in 1988 wrote an article titled “Amending Criminal Law? An Appeal for a Realistic New Orientation of Sexuality Politics” in which he advocated for the decriminalization of “pedosexuality”.

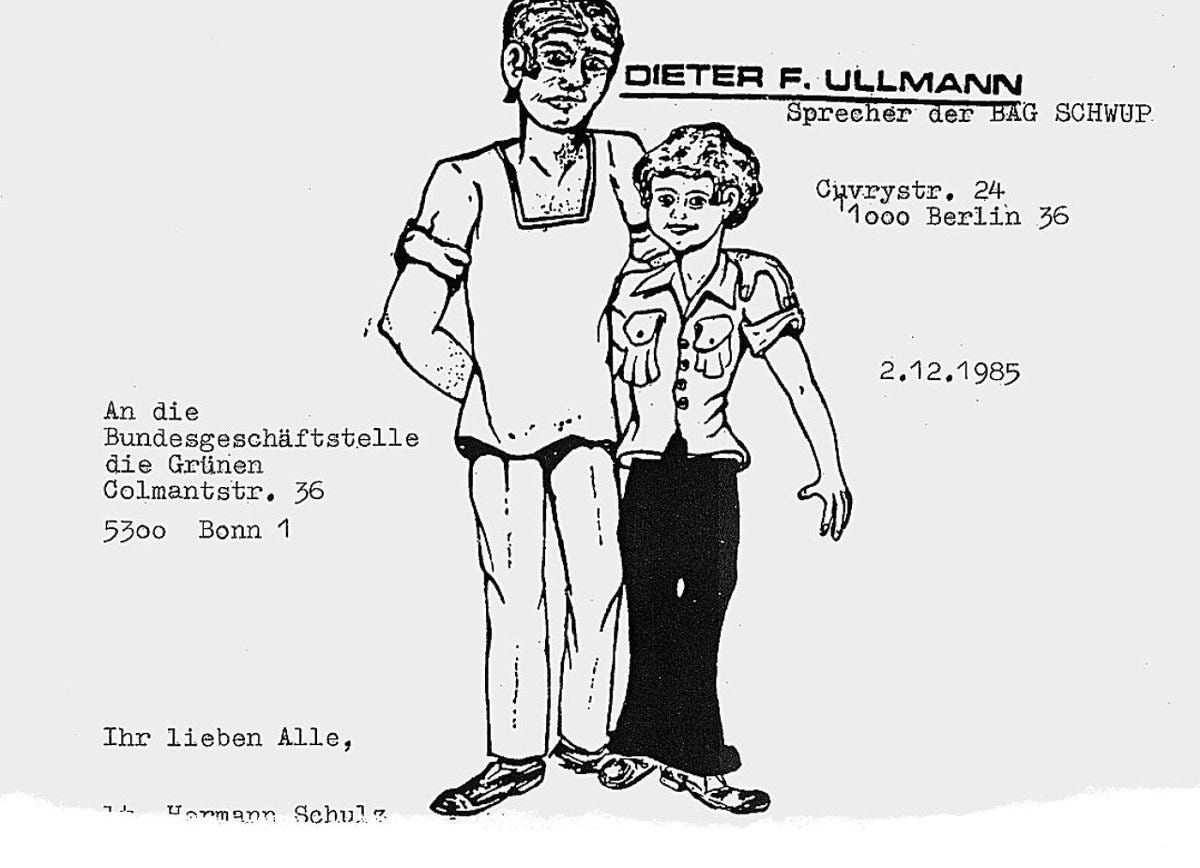

With victims coming forward and a rather ugly portrait emerging, the Green Party commissioned a report to investigate pedophilia claims in 2015. Its contents were shocking: some Green candidates had already been convicted of sexually abusing children at the time of their work with the party. One Green candidate for state parliament of Berlin, an unrepentant pedophile named Dieter Ullman, had run his campaign from prison, where he was serving time for child sexual abuse.

The report also revealed that a pedophile network operated within the Berlin branch of the Green party until 1995. It is believed that there are “up to 1,000 victims”.

The “pedo-sexuals” did not lose their influence in the Green Party until the mid-1990s. By then, the breakup of Yugoslavia was well underway, and was about to give the party a new taboo to break: Germany going to war.

End of part I. Your comments, as always, are welcome and appreciated.

Quite a story which I did not know ran so deep in Germany.

In the northwest I lived in a much saner corner of the counterculture where challenging taboos was much less part of it. We were forest workers and took our identity from that.

Curious to see where you go with this. Today the real subversive aktion seems today the province of the far right. Their provocations and perversions use the same ‘irony’. Only it’s antisemitism and misogyny they play with.